After spending two nights in Nagano photographing the snow monkeys of Jigokudani, we returned to Tokyo and took a flight from Haneda to Kushiro, Hokkaido. The main objective of this second part of our trip was to enjoy some wildlife and bird photography in Eastern Hokkaido. This area is growing quite popular among wildlife lovers and photographers, especially during the winter months—of which February is the busiest.

We kicked off our photography journey in Hokkaido with a two-night stay in Tsurui Village, home of the elegant red-crowned crane. First, we headed out for an early morning viewing session to Otowa Bridge—a place that is well known as a prime destination for observing these roosting cranes. There was a concern that the temperature would not drop low enough, as this year’s winter had proved to be comparatively warm, but it turned out to be a beautiful morning: the weather was clear and we had a crisp low of -16 degrees Celsius. As faint traces of daylight began to envelop the sky, the scenery became gradually more visible to us: we glimpsed frost-covered trees on both sides of the river, and spotted the red-crowned cranes sleeping in the water. Red-crowned cranes sleep standing up in shallow rivers because the temperature in the water is actually higher than on the snow, and also because it allows them to easily sense the approach of predators, like the red fox.

With the sunrise, the river filled up with an icy, steamy fog, against which the red-crowned cranes stood like shadowy silhouettes. On cold mornings, cranes are often slow to wake up. We observed them starting to move, and heard them gradually come to life as they woke from their slumber—singing, flapping their wings, and jumping up and down. It was a fantastic moment that was accompanied by a ceaseless symphony of camera shutters from the photographers lined up along the bridge. What a wonderful morning it was.

After breakfast at the hotel, we visited Ito Sanctuary, one of Tsurui village’s crane feeding stations. The arrival of the red-crowned cranes was very slow that morning, and even at 9:00 a.m., when the feeding began, only nine cranes had arrived. I was initially somewhat worried, but was relieved to see groups of red-crowned cranes begin arriving one after another. Watching the red-crowned cranes land gracefully on the snow in the soft morning light was a truly beautiful sight.

Afterwards, we had a wonderful time photographing these captivating birds on the snowy landscape. We captured moments of their courtship dances, and the beautiful way their breath turned white as they sang their lovely song.

After spending several hours photographing red-crowned cranes, we visited a forest where the nests of Ezo Ural owls can be found. On this day, we were lucky enough to see two owls lounging in their nest. According to the local guide, the second owl had just arrived two days prior to our visit. While we were absorbed in photographing the beautiful owls, a female Ezo-shika deer stared at us inquisitively from among trees.

After lunch, we went to the Akan International Crane Center, arriving just in time for the afternoon feeding. Not many Japanese photographers visit this place, but it is a regular stop for photographers hailing from abroad. Here, we had the chance to snap shots of not only cranes but also whooper swans.

The cranes here were not very active this afternoon, so we didn’t linger and opted to head back to Ito Sanctuary.

In the evening, we took plenty of photos of the red-crowned cranes as they gradually flew off to their nests. Unfortunately, it didn’t snow very much during these two days. It would have been ideal if we could have photographed red-crowned cranes against a perfect, winter wonderland landscape. Clear skies may improve visibility, but they provide us with very little snow, which can be a downside when it comes to wildlife photography in winter.

The red-crowned crane was once thought to be extinct, but recently the population has recovered, rising to about 1,800 in Hokkaido alone. We have the efforts of many people to thank for the renewed proliferation of the red-crowned crane. It is due to their hard work that we are now able to witness these magnificent birds for ourselves.

Image & text : kengo Yonetani

Observation : Feb 2025

*Contact us, Saiyu Travel for more information about wildlife and bird watching in Hokkaido. We can make various arrangements for your trip.

* We have a guesthouse, Shiretoko Serai, in Rausu, Shiretoko Peninsula.

*Youtube : Wildlife of Japan

Tags: Tsurui village, Bird photography of Japan, Shiretoko, Wildlife photography of Japan, Red-crowned Crane, Japanese crane, Tsurui mura, Wildlife of Hokkaido, Ito sanctuary, Wildlife of Japan, Crane photography, Wildlife Photography tour in Japan, Akan International Crane Center, Wildlife tour in Japan, Bird of Japan

Although they are resident birds, their numbers increase every winterdue to migration. They can be seen in reed beds and nearby rice fields, and return to their roosts in the floodplain at sunset.

Although they are resident birds, their numbers increase every winterdue to migration. They can be seen in reed beds and nearby rice fields, and return to their roosts in the floodplain at sunset. A winter bird, it can be seen in reed beds and nearby rice fields, returning to its roost in the playground at sunset. They are few in number.

A winter bird, it can be seen in reed beds and nearby rice fields, returning to its roost in the playground at sunset. They are few in number. They are resident birds, but their numbers increase every winter due to migration from the mountains. The most common species, along with the kite.

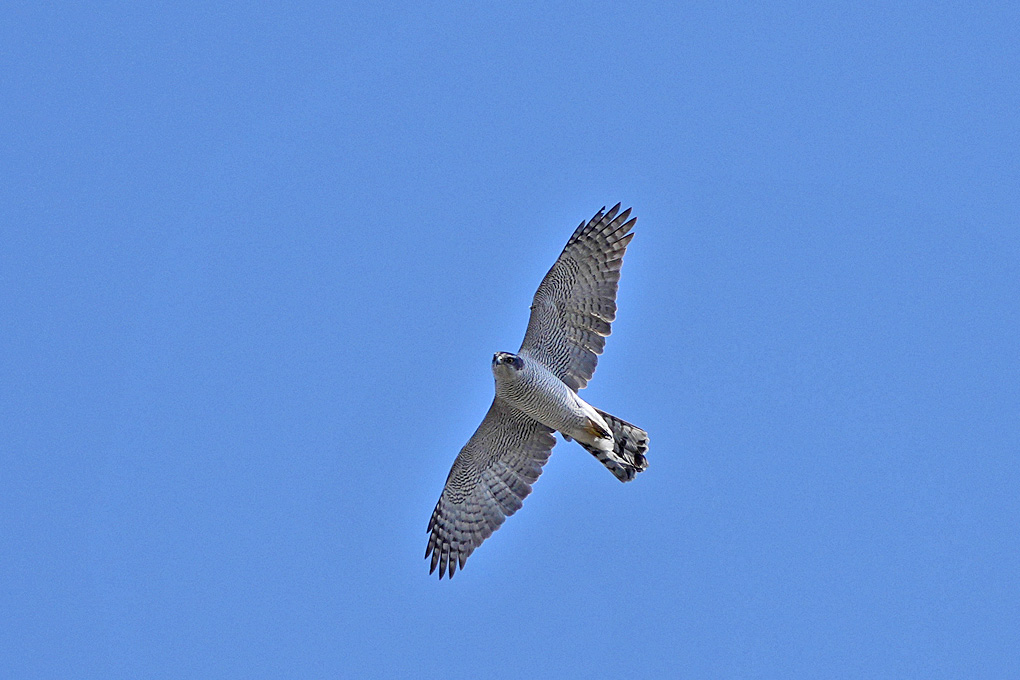

They are resident birds, but their numbers increase every winter due to migration from the mountains. The most common species, along with the kite. A resident bird, it can be seen flying in a variety of environments from forests to reed beds.

A resident bird, it can be seen flying in a variety of environments from forests to reed beds. A resident bird, here only in winter, it can be seen above the lake water and in the surrounding trees.

A resident bird, here only in winter, it can be seen above the lake water and in the surrounding trees. A resident bird, here only in winter, it can be seen in reed beds and nearby rice fields.

A resident bird, here only in winter, it can be seen in reed beds and nearby rice fields. Although they are resident birds, their numbers increase every winter due to migration from the mountains. They can be seen in reed beds and nearby rice paddies.

Although they are resident birds, their numbers increase every winter due to migration from the mountains. They can be seen in reed beds and nearby rice paddies. A winter bird, found in reed beds and nearby rice fields. Few in number.

A winter bird, found in reed beds and nearby rice fields. Few in number. A winter bird, it can be seen in reed beds at sunset. However, the location where they can be seen varies, as they are natural enemies of the tundra-winged teal.

A winter bird, it can be seen in reed beds at sunset. However, the location where they can be seen varies, as they are natural enemies of the tundra-winged teal. A resident bird, it is found here in the riparian forests in winter and spring. They breed in the spring and migrate after leaving the nest.

A resident bird, it is found here in the riparian forests in winter and spring. They breed in the spring and migrate after leaving the nest. A resident bird, several pairs successfully molt annually. Found near the water’s edge of lakes and marshes.

A resident bird, several pairs successfully molt annually. Found near the water’s edge of lakes and marshes. A beautiful winter duck, found in lakes and marshes.

A beautiful winter duck, found in lakes and marshes. A beautiful two-tailed winter duck, found in lakes and marshes.

A beautiful two-tailed winter duck, found in lakes and marshes. A large winter plover with beautiful metallic luster feathers. They can be seen in rice paddies and low grasslands.

A large winter plover with beautiful metallic luster feathers. They can be seen in rice paddies and low grasslands. A large resident plover, found in rice fields and low grasslands. Few in number.

A large resident plover, found in rice fields and low grasslands. Few in number.

A beautiful little bird found in reed beds and grasslands.

A beautiful little bird found in reed beds and grasslands. Seen in reed beds, they look for insects while splitting reed stalks.

Seen in reed beds, they look for insects while splitting reed stalks. Found singly or in pairs in riverside forests.

Found singly or in pairs in riverside forests. Found in groups or singly in riparian forests.

Found in groups or singly in riparian forests. Found in reed beds and around deep bushes, they are easy to see in March during the breeding season.

Found in reed beds and around deep bushes, they are easy to see in March during the breeding season. Found around reed beds and deep bushes. Bringing children along is not advised.

Found around reed beds and deep bushes. Bringing children along is not advised. Found around reed beds and deep bushes. Other predators include the red fox, Japanese weasel, and the non-native common raccoon.

Found around reed beds and deep bushes. Other predators include the red fox, Japanese weasel, and the non-native common raccoon.